|

A 15-year old boy with good reason for not saying

his name is talking about his experience at Yerevan's

Special School No. 18.

"God forbid what will happen if they catch

you when you escape," he says. "Muradyan

was stripping us, pouring water on us and whipping

us. If we decided to escape then we'd just as

well have dug a grave for ourselves. Once I escaped

at night but they caught me. The night man put

a piece of parquet on my hands and stood on that

parquet.

"A few boys once were caught when they were

trying to escape. The night guards spat and pissed

on those boys. I wish this school were blown up."

School No. 18 is one of two special schools in

Armenia for children who exhibit "socially

dangerous behavior" as defined by the Ministry

of Education and Science.

Children between the ages of 7 and 12 who have

committed theft or other minor crimes are sent

to the special school (with the consent of their

parents) until they finish 8th form (at about

age 14). Additionally, orphans and children caught

begging or for vagrancy are sent to No. 18.

The school is located in the Nubarashen district

of Yerevan, and currently has 95 pupils, most

from extremely poor families.

Acting on information received of routine abuse

and mistreatment, ArmeniaNow interviewed former

and current students as well as school officials

to obtain the following report.

The recollections of the 15 year old is not the

only report of abuse at the school. ArmeniaNow

has talked with six youth who were placed at No.

18 at different times during 1997-2003. They talk

of beatings, of lockups, of having food withheld

and of being forbidden to meet with parents.

For the past 23 years School No. 18 has been

under the direction of Zhora Muradyan, who previously

was an assistant at the State Prosecutor's Office.

ArmeniaNow spoke with director Muradyan. He denies

all accusations of inappropriate conduct by the

school staff.

The Safaryans

Araik Safaryan is 16. His brother Stepan is 12.

In 1999, police saw the Safaryan brothers dressed

in dirty clothes and traveling alone in a Yerevan-Kharberd

bus.

Police went to their home in Kharberd on the

outskirts of Yerevan and told the boys' mother,

Hripsimeh, about a special school in Yerevan where

her boys would receive a proper education and

upbringing.

Hripsimeh, a single mother of five sons, gave

her consent.

"The policemen praised the school and said

that it was a strict school and children would

be educated there very well and that I would have

few problems. I couldn't take care of all of my

children so I agreed," Hripsimeh says. It

is a decision she now regrets.

Stepan, then 8 years old, was not attending school

because his mother couldn't afford to send him.

He was happy for a chance to go to the school

the police told about.

"It was one of the first lessons. I couldn't

write 'N' letter very well and the teacher hit

me and my nose bled," says Stepan. "I

cleaned blood with my handkerchief. Muradyan told

me to visit his office and when I came he gave

me a slap. I told I would write a letter to my

ma and tell her that you beat me here. He said

if he knows that I did something like that then

he will tear the letter and me."

For two years Hripsimeh had no idea that her

sons were living in a school where, her son say,

they and other students were routinely mistreated.

Only once in a letter to his younger brother,

Stepan hinted that the boys were in an undesirable

place.

"Andranik-jan, I wish you never meet bad

people in your life," the letter said.

|

|

The

Kudashin brothers say their time at Special

School 18 was not so happy.

|

Araik limps and his ankles are swollen. He says

that he still suffers from wounds inflicted by

Murad Muradyan, who is the director's son, and

vice-principal and physical education teacher.

"When we stood in line, he used to approach

us and kick my ankles. My legs were terribly aching,"

says Araik. "Once I told the doctor about

it but he said that I'm lying and sent me back

to class. I lost consciousness from pain, I didn't

remember anything. Then they called an ambulance."

According to the Safaryans and others, pupils

were punished for different reasons: when they

couldn't sleep and were talking lying in their

beds, when they didn't learn their lessons, when

they tore books, smoked, collected fruits in gardens

and for other reasons.

"I didn't eat a meal with onions in it and

gave it to a boy sitting next to me," Araik

says. "The cook told Muradyan about that

and he threw the meal in my face. He did that

three times."

Once Araik ran away from the school after not

being allowed to visit his mother. Hripsimeh sent

him back to school where, Araik says, Zhora Muradyan

stripped him, beat him with a belt and poured

water over him.

Students at No. 18 were under strict orders not

to tell parents anything about the school.

"I didn't know what was taking place in school,"

Hripsimeh says. "Children didn't tell me

anything. When Araik escaped I was very angry,

until I saw Stepan's blood soaked handkerchief."

It was Stepan's second blood soaked handkerchief.

This time he says it came after staff woke the

students in the middle of the night to discipline

some boys for talking after lights out.

"They put us into line and began giving

slaps. I fell aslept standing in the line and

fell down on my face. In the morning my nose swelled

but it didn't bleed. The doctor took a look at

the nose and said that it is broken but everything

is fine and I can go to classes.

"It was the lessons of Armenian language

and I didn't learn my lessons well enough. Teacher

Khachatryan gave me a slap and my nose bled. All

my clothes were soaked with blood. I put a handkerchief

on my nose but it didn't help."

Stepan kept the handkerchief until he finally

met his mother, as silent evidence of things he

was afraid to tell about.

After learning what had happened Hripsimeh took

her sons from the school and handed in an application

to the Ministry of Science and Education requesting

to transfer her children to another school. Now

Stepan studies in Kharberd and Araik works in

a market.

The family claims that Murad Muradyan and one

of the guards came to try to take the boys back.

"They were cursing and insulting,"

says the boys' grandmother, Maria. "They

said 'How can the children live in a house like

this?' (Seven Safaryans live in a small wagon).

And I told them 'How can I give my children to

you; you made them invalid."

The Kudashins

|

|

Boys

currently at the school say that everything

is fine.

|

Fifteen year old Roman and 16 year old Vasiliy

Kudashin spent six years in No. 18. In 1997, when

they were age nine and 10, the brothers were caught

stealing, and sent to the special school.

During their time at No.18, their father died

and their mother went missing. Last January Vasiliy

escaped from the school for the fourth time and

was ordered to an orphanage in Vanadzor.

The brothers remember the Nurbarshen school as

a place of constant beatings.

"There wasn't such a day when someone wasn't

beaten. We were beaten everyday," says Vasiliy.

In September 2002 the brothers learned from an

acquaintance that their father had been dead for

two years. The boys say that the director knew

about their father's death when it happened, but

did not tell them.

Upset at finding out the news, and to escape routine

punishment, one night the boys jumped out their

third-floor bedroom window into a fir tree. When

Roman hit the ground he injured his kidneys.

Once a pupil at the school tried to open the

door of a storehouse, however he couldn't open

it because the key broke off in the lock. Vasiliy

says that he found another part of the key and

Zhora Muradyan saw it in his hand and decided

that Vasiliy was the one who tried to open storehouse

door.

"I told him that I didn't do that but he

said I broke the key and he was beating me all

day long. That day wherever he saw me he beat

me. He was beating me with hands and legs and

kicking my legs.

"Later he found out who tried to open the

storehouse. But he continued to beat me as he

wanted me to tell the names of those who broke

the key. I didn't know who broke the key but even

if I knew I wouldn't tell him."

The brothers say that Zhora Muradyan used a stick

with a thin piece of rubber attached as a whip

for the students.

When the brothers escaped to their home, they

found other people living there. The police took

them back to No. 18. This time, though, they were

not beaten.

"I was hurt (from the fall from his window)

and the cops told (Muradyan) that if he again

beats us they would put the law on him. Muradyan

was scared," says Roman.

According to Kudashin brothers, the director

used beatings to force children to snitch on each

other.

"He liked very much to question children,"

Vasiliy says. "He was beating until someone

shouldered all the guilt."

Roman describes the director with one word: "He

is a sadist."

Oddly, though, Roman has a positive attitude

about one aspect of being at No. 18. He says that

the fear of punishment forced him to become a

good student. In Vanadzor he says he doesn't learn,

because no one will punish him if he doesn't.

The director of the Vanadzor orphanage, Arshaluis

Harutyunyan, says both Kudashin boys are well

behaved and that they have created no problems

in their time at the orphanage.

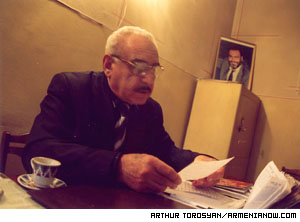

The director

Zhora Muradyan, age 64, has been director of

School No. 18 since 1980 and director of Hankavan's

"Hasmik" camp for children and teenagers

(a Pioneer camp during Soviet times) since 1968.

Before independence, the number of students at

No. 18 never exceeded 15.

"During Soviet times children were caught

for playing cards and brought here," says

Zhora Muradyan. "They were brought here also

for being involved in fighting and knifing. We

never had children here who were real criminals

and had already had an experience of life in the

criminal world."

The 95 pupils now at the school do not include

any picked up for breaking the law. And last year,

for the first time, girls (6) were placed in the

school.

The school is surrounded by walls. Anyone entering

must pass through a checkpoint.

In the back of the school are a fruit garden

and fruit trees. Muradyan remembers that before

he became director there was no time for apricots

to ripen as children used to steal immature fruits.

These days the orchard produces a bumper crop.

Silence reigns in the school. As the director

says: "When you enter the building you see

that everything is perfect starting from the cleanness

and ending with the order."

The building was reconstructed 18 years ago,

yet the classroom walls remain spotless. Chairs

are also clean and without any graffiti. The bathroom

was reconstructed by the Armenian Evangelistic

Church. Nongovernmental organizations can render

humanitarian assistance, but Muradyan refuses

any form of psychological, educational or social

help.

When one lesson is finished, children form lines

and go to the next.

"Hey, man, you have problems with lines?

In other places as soon as the bell rings children

begin squabbling. But here when ring bells each

child stands in line and goes to another classroom.

You think it is a bad tradition?" asks Zhora

Muradyan rhetorically.

None of the staff confirms reports of beatings

or abuse.

Deputy principal of the school for educational

activity Haykanush Javakhyan, who, according to

the Sarafyan brothers, was constantly beating

them, says that no acts of violence are committed

in the school.

"We always hear words of praise from parents,"

he says. "They see big changes both in behavior

of their children and in their educational level

and in their discipline. There are no beatings

at all. How can we beat these children?"

Murad Muradyan insists on the same.

"Of course, beatings are not administered

here, they were administered in Ter Todik's school

(made famous in a popular Armenian writer's biography).

Children must simply be busy with something always.

During the lessons they must be busy with lessons,

during the games - with games and during the work

- with work. Commanders of military units say

that a soldier is a potential criminal if he is

not busy with something. The same with children

because if they are not busy with something then

they start thinking about other things."

|

|

The

grandmother says the school made the boys

"invalid"..

|

The school has a military-patriotic bias. Different

hobby groups are functioning after classes such

as home land protection, military art, cutting

and sewing, shoemaking and painting.

Hrachya Manukyan, 21, is a graduate of the school

and now is employed as a night guard there. He

tells a slightly different story about discipline

at the school.

"Yes, I agree I slap (the students),"

he says. "But who were older than me slapped

me, but they did it for my good. They did it because

I was wrong. I felt that I was guilty and I deserved

that slap. t is better to get a slap than in the

future to sit behind the bars and be beaten with

truncheons."

Manukyan has no professional education, however,

it doesn't bother him.

"People can have diplomas but they must

have diplomas in their hearts. We already have

pedagogical education more or less. We have learned

from our teachers."

When staff members talk about advantages of the

school nobody forgets to mention several times

that everything has been done thanks to Muradyan,

who, as Javakhyan describes him, "is a real

man."

Muradyan doesn't consider beatings to be his

main educational method.

"Can you keep children in school by beating

them," he asks. "If you beat children

they won't obey you and won't comply with your

orders."

However, he doesn't deny that from time to time

he administers corporal punishment.

"I can't educate children without punishing

them," he says. "If a child did something

which made everybody angry and if I don't give

that child a slap then I won't be able to educate

others. It can happen once a year."

He regards himself as a follower of strict educational

methods. He says that one must be exacting and

strict with children but at the same time attentive

and helpful.

Muradyan says that he demands three things of

new pupils: "You must learn well, model your

friends' behavior and demonstrate exemplary conduct.

And the third, come and confess to whatever you

did."

And, according to Muradyan, if someone doesn't

confess then his friends tell him to do that or

they go and tell the director themselves.

"One of the little children once dirtied

the wall. You should have seen what other children

did with him, they said: 'Mr. Muradyan, he dirtied

the wall and we could hardly get it clean."

According to him, school administers punishments

such as reprimand, serious reprimand, or children

are not allowed to participate at different measures,

for instance, they are not taken to theatre.

Punishments

Pupils tell about different methods of punishment.

If eating is considered to be a measure of reprimand,

then Muradyan and the pupils talk about the same

things because, according to them, the most popular

punishment is depriving of food.

Vasiliy: "Once a few boys tore covering

of chairs and 20 boys had been deprived of food

for one week. There was a boy, Artur, he was so

hungry that was eating walls. He was taking off

pieces of plaster from the wall and eating them.

My brother would bring bread for me and I ate

only bread and drank only water. "

Roman: "Once a boy tore a book and I was

deprived of dinner. Everybody ate four times a

day but I was allowed to eat only two times. Sometimes

it happened when for not learning lessons we were

deprived of food during the whole day."

Stepan: "When someone talked during the

dinner with another boy sitting next to him then

he was deprived of food. There was a special register

in the school. They put a mark next to your name

and forbade you to eat during the whole day. I

was deprived of food very often. If I had something

good, for instance, sport uniform or trousers,

then I exchanged it for food. There were boys

studying in eighth form, who would go and tell

Muradyan that we exchanged clothes for food and

they would come and beat us. Araik would often

bring food for me. Once my friend was deprived

of food, I chopped bread into the pocket of my

jacket and took it to him. Night people came to

check our pockets, I threw my jacket into the

neighboring room. So they didn't find bread and

left. Then I gave bread to my friend and told

him to eat quickly as they could return and check

again. As soon as he finished eating they returned

and saw crumbs of bread on the floor. They beat

everybody in the room."

Another alleged method of punishment is when

everybody is punished for someone's fault or when

everybody punishes someone.

Muradyan denies such charges.

"Children, themselves, don't punish someone.

There is nothing like that here. If a child did

something wrong they tell him to go and confess

himself and if he doesn't then they will tell

who did that."

|

|

"Ask

the children", the director says.

|

However, boys say that voluntary nobody wants

to snitch on anybody.

Roman: "If someone was snitching then we

were finding reason to beat him and we told him

to go and answer for whatever he did. And after

that he never snitched. But we didn't know always

who was snitching."

Stepan: "Children of the whole school were

put in two lines and the delinquent child was

ordered to walk through these two lines and we

were ordered to beat him and spit on him while

he was walking through the lines. And we were

beating. If we didn't beat him then we would be

punished the same way."

Araik: "Once we must have learned something

by heart and I didn't learn it. Muradyan came

and asked who got a bad mark. I was one of those

with a bad mark. He ordered everybody to stand

in two lines and made me walk through those lines

and boys were beating me. When I reached him he

hit my belly and neck and deprived me of food

for the whole day".

The boys say Muradyan had an "all for one

and one for all" motto which forced everyone

to punish the one who misbehaved.

Vasiliy: "At night, at 12:00 or 1:00 when

someone was talking in the room they woke us up,

put in a line and beat us. Sometimes it happened

when they put a child, who was talking, in the

middle of the room and the entire line, 80 children,

were beating him. If we didn't beat him then we

would be beaten. Once they put us in line and

all of us began hitting a boy. When it was Igor

Pisarev's turn to hit that boy he refused. They

told him that if he didn't hit him then he, himself,

would be beaten more severely. He didn't, and

he was taken away and beaten severely for not

following orders.

Roman: "When someone escaped they woke us

up at one o'clock at night and asked who knows

how he escaped and began beating us. There was

a lad, Liova Hakobyan, he was a teacher of crafts

and night guard as well. He used to open window,

strip us and put us next to it. We were freezing.

Then he was soaking wooden sticks in water and

beating us."

All the boys tell of an isolation ward. The 15-year

old who is afraid to give his name says he spent

an entire day in the ward, dreaming of seeing

Muradyan being beaten in the ward.

Escapes

Zhora Muradyan assures that over the years children

have escaped from school only two times. However,

children tell that there were many escapes and

sometimes there were even cases of mass escapes

by seven or eight children.

According to the former students, punishment

for escape is the most severe. Those who consistently

try to get away are sometimes urinated on by night

guards. Still, attempts are often the boys say.

Some who are afraid to escape look for other

ways to leave.

One boy, Levon, had an artificial eye. He took

his eye out and put it in the wing of a door,

so that it would be broken and he could go home.

But the eye didn't break, and Levon was beaten

for his attempt.

One 15 year old says he faked appendicitis, hoping

he'd be sent home. But he was operated on and

sent back to the school.

Back at the school, he put dirt in the incision

so that it became infected. He was sent back to

the hospital for treatment, and escaped from the

hospital.

The boys say that conditions weren't as bad at

Camp Hasmik, where other children mixed with the

students. But some tried to run away from the

camp, they say, and were severely punished for

the effort.

Roman: "When someone was caught escaping

from the camp he was tied to a tree near the river,

then they soaked a whip in the water and began

beating him."

The boys told about one student, Hayk. He escaped

but Muradyan, they say, went to Hrazdan by car

and caught him there. Word among the students

is that Muradyan tied him near the river, stripped

him and beat him with a wet whip and then locked

him in the trunk of his car for the bumpy drive

back.

ArmeniaNow relayed the accusations to Zhora Muradyan.

"Ask the children," he said, then produced

a letter from a 14-year old student Robert Shahinyan.

"Dear ma, don't' visit me. I have everything

I need here. They take care of me here and I know

Mr. Muradyan will find a place for me as he is

my father. Dear ma, I love you very much but I

love Mr. Muradyan a little more than you."

The former students who talked to ArmeniaNow

say that, if while they were still students, anyone

asked them about conditions, they would have said

the school was great. Otherwise, they say, a list

of punishments would be applied.

It is impossible to find a single pupil in school,

who will point at any defects. Everybody repeats:

"It is very good in school. Everything is

good. There is nothing bad happening here."

On a trip to Yerevan with the director of their

orphanage, the Kudashin brothers met one of their

classmates in a Yerevan market (during summer

when the boy had been allowed to leave the school

for some days).

The boy said he is trying every way possible

to get out of No. 18. But, later at he school,

the same boy told ArmeniaNow: "I have no

problems, everything is very good "

Parents

The director assures that parents can meet with

their children whenever they want. However, there

are cases when he forbids meetings.

|

|

Boys

say that Murad Muradyan, the director's

son, is known for strict discipline..

|

"A parent came to see her child. The child

enters my office and says: 'My ma came drunk,

I don't want other children to know about it.'

What should I do?"

But Hripsimeh Sarafyan says she was not drunk

or otherwise objectionable when Muradyan refused

to let her visit her boys.

"When I went there for the first time to

see my children he said: 'You won't see your children

until you demonstrate good character'," she

says. "I didn't understand what he meant

by 'demonstrate good character.'

"So I had been going to school for one week

and returning from there with tears in my eyes.

He was forbidding me to see my children if only

to make sure that they are in that school. I couldn't

take it any more and one day I made noise there

asking what was the reason that they were forbidding

me to see my children. He said that they don't

allow children to meet with their parents if parents

are drinkers or drug-addicted. I said I will sit

here until a doctor comes and examines me and

if that doctor finds traces of alcohol or drugs

in my blood then I will disown my children, but

if he doesn't find then you will answer for that.

After I said that he softened."

One boy's mother says that she had been visiting

the school every two weeks, but that Muradyan

told her that she couldn't come that frequently.

So she started going once a month. One boy says

he didn't see his parents for three to five months.

Muradyan confesses that he forbids some children

to go home as they can commit thefts on their

way.

The Ministry of Education and Science is aware

of disciplinary methods at Special School No.

18, from complaints made by a few parents. The

ministry is aware, too, that it is illegal for

a child to be refused the right to see his parents.

Still, the ministry has not investigated charges

of physical abuse or abuse of rights.

Chief specialist of the ministry Anahit Muradyan

(no relation to the others) says that she heard

about acts of violence but she has no "official"

information on the matter. She says that first

of all a definition must be given to violence.

"In accordance with previous legislation,

slapping wasn't regarded as an act of violence."

The Government of Armenia has no guidelines for

regulating discipline in its schools. Consequently,

directors of schools administer their own methods

for educating children. According to Anahit Muradyan,

it is natural when different institutions administer

different methods. She thinks that schools like

the one in Nubarashen are necessary.

"There are numerous educational methods

in the world," she says. "Who said that

only one method must be administered in all of

Armenia?"

Anahit Muradyan considers it an effective method,

for example, when students at No. 18 punish other

students, so long as a child's rights are not

limited.

She says, too, that some directors exercise too

much ownership of their students. In previous

times, she says, the directors were considered

guardians and not just educators of such children

and would use personal methods of child rearing.

"Directors of schools have no right to replace

parents," she says. "Educational institutions

help parents only to organize their children's

education and sometimes during that process it

becomes necessary to offer care services. According

to legislation, only parents have the right to

decide anything for their children."

Today there are 52 special educational institutions

in Armenia where some 11,000 children live and

study. Twenty six are for orphans and children

deprived of parental care.

Over the past three years the Assembly and Transferring

Center for children has sent eight children to

Nubarashen. Two later committed crimes for which

they were sent to prison. (The Center works with

3 to 18 year olds living in unsuitable conditions.

After three to five months at the Center, the

children are sent to different educational institutions.)

"The makeup of children who were sent to

special schools has changed over past 10 years,"

says psychologist of the Center Karen Harutyunyan.

"In the '90s there were specific antisocial

groups of children who mainly committed thefts

and they were sent to special disciplinary schools."

But Harutyunyan says that in the past three years,

street children are mainly those who are not out

to commit crimes, but who are forced to be there

because of social hardship. Meanwhile, however,

staffs of special schools have not changed their

methods to match the change in the kind of child

who ends up in their care.

"If children who appeared in hard social

conditions are subjected to violence then probably

these methods are sadistic," the psychologist

says. "I'm sure that the entire staff of

Nubarashen cannot have sadistic impulses. However

if methods that were used before are still in

use then the staff is so isolated from the outer

world that they still continue to stick to the

methods of work with 'children-criminals'."

Harutyunyan says he has visited School No. 18

over the past three years and that, even in private,

no child has ever expressed oppression. At the

same time, he has met boys who previously attended

No. 18 and recall it as an emotionally difficult

experience.

He says he has heard the explanations for why

parents are refused visitation rights.

"If they kill a parent in the heart of a

child then the rebellious feeling against the

loss will arise in a child's heart and it can

be resulted in acts of hooliganism, sadness, despair

and desire for escapes.

"At the same time I want to let everybody,

especially human rights activists, know that it

is impossible to help children to resolve all

their emotional problems and overcome all difficulties

connected with their behavior only by calling

for protection of children's rights. Also, these

institutions need good specialists of psychology,

who will help in resolving the children's problems."

|