|

|

The

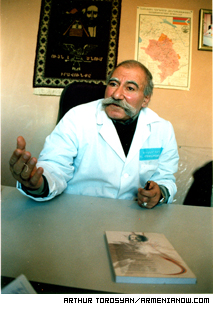

doctor says he sacrificed a surgical practice

"for this land".

|

Is it possible that a pilot of an SU fighter

plane would choose instead to fly the "kukuruznik"

(the simple Russian plane nicknamed "corn

cutter")?

Surgeon Artsakh Buniatyan pours mulberry vodka

into glasses and compares himself to a fighter

pilot. The doctor has exiled himself from a modern

hospital in Abovian to this "kukuruznik"

of a place, Kashatagh, where there are no facilities

for surgery.

"I sacrificed my surgical practice for

this land," he says and drinks his first

glass.

(Before being reclaimed during the war with Azerbaijan,

Kashatagh - still widely known as Lachin -- was

the Azeri territory separating Karabakh from Armenia.

Through heavy fighting, Armenian forces took the

territory in 1992, and in 1993 began repopulating

it, and rejoining Karabakh and Armenia after 70

years of separation.)

Mulberry vodka ("t-ti oghi") is brewed

by villagers of Karabakh and the southern regions

of Armenia and is the potent and favored drink

of the region. And so it is in Kashatagh, the

newest region of Karabakh.

Head of the Kashatagh Medical Division and director

of Berdzor (Kashatagh's administrative center)

hospital, Artsakh Buniatyan named the vodka liquid

sun.

"Liquid sun is a divine drink, when you

drink it you destroy it, that's why you must meditate

while you drink it," says the doctor and

then blissfully concentrating his eyes on the

liquid in the glass he addresses it: "After

I drink you, you will turn in my body into balm,

you will heal me, you will free me from bad thoughts

and make me more kind-hearted. After you drink

it you must not twist you face as you can hurt

it."

Then the doctor drinks another glass, cleans

his long fedai mustache and smiles. People sitting

around the table mechanically repeat everything

he did. Despite the hard (70 percent) drink, his

guests swallow without a flinch. Then they chase

the fiery liquid with apple.

With his every guest the doctor performs three

meditations in his small office in Berdzor hospital.

Vodka is one of those rare gifts that he accepts

from villagers.

|

|

Patients

say he has "magic hands, not to mention

his heart".

|

Berdzor hospital may be the only hospital of

the "two Armenias" where medical treatment

is really free of charge. Patients don't pay anything

while being treated in the hospital (in other

hospitals of Armenia relatives of patients must

bring all necessary things for patients from linen

to medicines and food and must pay doctors and

nurses in cash for treatment).

"If a doctor takes money from a patient

then he will be punished for that," says

Buniatyan. "However, we can't treat all diseases

and when we send a patient to Yerevan or Goris

then he finds himself in a completely different

world and falls into the hands of hawks, where

they demand money and medicines of him. In those

places residents of Kashatagh are taken for third

rate people, who cannot cover their treatment

expenses."

Artsakh Buniatyan is 69. During the entire Karabakh

war from 1992 to 1995 he was working as a doctor

in a field hospital. He published three books

about the years he had spent during the war. He

is author of five books, one of which is a book

of poems.

After the war he again returned to his former

work in Abovian hospital.

"I hadn't seen my family for three years.

Three daughters were waiting for me. After the

slaughter of war, it was hard for me to adapt

to civil medicine." While he was trying to

adapt he was invited to Kashatagh hospital's opening

ceremony.

"I was invited to spend two days there,

but they lied to me. At the opening ceremony the

Karabakh Minister handed over the order of appointing

me to this position. I thought that during the

war I had been in so many difficult places and

now it is God's will and it means that people

need me."

Officials congratulated Buniatyan and left him

alone with the walls of the hospital.

"For many months I had been spending more

difficult days here than during the war. There

was no place here to render patients medical assistance.

People were blown up on mines and it was terrible

that we couldn't help them."

These days the hospital is a modest resting place

for whatever conditions afflict the residents

of the region.

Women who've come from remote villages to deliver

babies lie next to each other in one ward of the

small two-storied building.

Seventy-year-old Emma is sick with cancer and

has been in the hospital for two months. Her illness

is terminal and now she waits to die.

Roza lies next to Emma. She has a kidney ailment

and is waiting for her husband to sell a calf

so that they'll have money to take her to Yerevan

for treatment.

Three children who have pneumonia are in the

same ward, brought there from a remote mountain

village.

When the doctor appears, he is met with praise:

"He has magic hands. Not to mention his heart,"

a patient says.

An operating room is the only room facing the

street and it differs from any other ordinary

room, as it has two ceiling lamps instead of one.

"Dust from the streets penetrates the room

but we can do nothing. Fortunately cases of complications

haven't been noticed," Buniatyan says.

The simple room's equipment - a device to administer

anesthesiology -- was a gift of Agape, an American

charitable organization. But the equipment has

never been used, because the hospital doesn't

have an anesthesiologist. An appendectomy is about

the most serious surgery that could take place

here.

Buniatyan is not a gynecologist, however he

delivers babies and treats some female illnesses

as there are no specialists of this field in the

hospital. The maternity department is a three-room

ward. With her newborn child a mother lies in

one bed placed in the hall connecting the rooms.

There is no other bed for putting the newborn

separately.

For eight years in this building adults, children,

women and men have been treated next to each other

resignedly like a Gypsy band, as Buniatyan says.

The entire region looks like a mixed strolling

company. "This territory hasn't got its distinguishing

features yet," says Buniatyan. "People

brought their traditions and one common mentality

hasn't been shaped yet. People who appeared in

the most difficult situation came to live here.

Each of them suffers and has problems. There are

people who lost their homes and found themselves

in the streets. They came here to find a shelter."

Eight doctors work in the hospital and they render

medical assistance to residents of half of the

region (there is another hospital in the south

in Kovsakan). They earn 45,000 drams (about $80)

a month. Buniatyan dreams that one day young doctors

will come to the region and he will be able to

pass on his experience to them. It is almost impossible

to find a doctor who will agree to work in the

region as nobody wants to come here and work only

for salary without taking money for treatment

from patients.

"During the entire history of Armenia people

have always been taking care of doctors giving

them hens, eggs. But now doctors are simply tearing

up their patients, they became leeches. Forget

about Hippocrates, they kill him 10 times,"

says Buniatyan, whose sorest subject is corruption

in the healthcare system. "There are villagers,

who with great difficulties purchased two cows

in 4-5 years but when they get sick they have

to sell these cows to pay doctors in Yerevan for

treatment. People prefer to die but never visit

a doctor."

He fears that authorities will start charging

facility fees in this hospital, like many in Armenia.

There is one medical service, which the doctor

refuses to provide . . .

A woman approaches Buniatyan and speaks to him

in a low voice. Her husband stands behind her.

Buniatyan whips out a reply: "No way, it

is forbidden here."

The woman says she has three children and can't

take care of them. She wants an abortion.

"I don't care, you will have the fourth,"

says the doctor leaving them embarrassedly standing.

Buniatyan made two rules for the hospital. The

first: No abortions.

"Two of 10 women go to Goris to have abortions,

while eight give birth to children and then come

to me and thank me because I didn't kill their

fetuses," says Buniatyan (from 140 to 160

children are born in the region annually).

Rule Number Two: Any baby born in Buniatyan's

hospital must be given an Armenian name. A list

of names is attached to a wall in the hospital

from which parents may choose.

After inspecting the hospital the "fighter

pilot" returns to his office and pours liquid

sun into glasses.

"When we have guests, the batteries of our

soul get charged and then when villagers visit

us we charge them in our turn. They are poor people,

who come to the big city and the city is Berdzor,"

says the doctor, and empties his glass in one

sip.

|