|

|

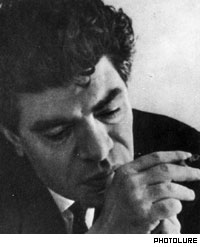

The

poet

|

Last February when thousands demonstrated against

presidential election violations, passionate speeches

from politicians were followed by actor Vladimir

Abajyan's, who recited a poem: "People are

different"

What he likes most of all,

Best of all in his life,

Is his... chair.

He loves it,

He woos it,

He creeps to proceed,

At all costs he crawls to it,

And thus he climbs up to sit

on the shoulders of the world.

The words belong to Paruir Sevak, and perhaps

no others could be so in tune with speeches about

seizure of power, fraud and injustices. And even

if another such poem does exist it probably is

one of Sevak's.

January 26 marked the 80th anniversary of Paruir

Sevak's birth.

Conservatory teacher of Armenian language Biurakn

Andreasyan says that for 20 years students have

been naming Paruir Sevak and Vahan Teryan as their

favorite poets and, without waiting for their

tutor to give them homework, with great pleasure

have recited Sevak by heart.

The poet died 33 years ago, but Sevakamania is

still alive.

"Sevak makes you think. You cannot read

his works just mechanically. After you read them

you start thinking of people's states of mind,

hypocrisy, different expressions of love, faith

and history of Armenia," says 18 year old

Gayane Melkomyan. "His comparisons are very

unique, his works are both simple and complicated."

Unlike the flowery, pastoral images and landscape

metaphors of his contemporaries, Sevak's Armenia

is the modern city and urban spirit - calculators,

trams, theatre and concert bills attached to walls,

airplanes and so forth.

His poetry explains in a simple manner the unexplainable:

"First love is like first loaf, it always

burns and you can't help it."

"I hate your name as you probably hate

my hands that used to stroke you

if I have

a girl she will bear your name . . ."

"You - three letters, you - an ordinary

pronoun but with these three letters I become

an owner of this entire world."

But coupled with this simplicity is a clever

layering that reveals hidden possibilities from

the Armenian language. Many poets wrote their

first lines, influenced by Sevak's catchy rhythms

and precise words.

Later, though, some of those protégés

criticized Sevak's work as being too commercial,

written with exaggerated civic pathos and overdone.

(He is among the most wordy poets, as was evidenced

by the publication of a two-volume glossary of

words used by Sevak.)

Sevak's obstinate spirit boils the blood of youth,

captured in such phrases as:

"Without going mad nobody would win

and words would never turn into songs if they

didn't go crazy

I wish I were always crazy."

And:

"I would like to erase the word 'cautious'

at the expense of life."

"I would like to turn irregularity into

a rule."

If the Western youth movements of 1960s were

reflected in Armenian poems, the epoch of that

era would be Sevak's poetry books "The Man

in the Palm of Your Hand" and "Let There

be Light", which are the wreath of his creative

work. It is a poetry against bureaucracy, philistinism,

moral dogmas and hypocrisy.

There was little or no dissident literature in

Soviet Armenia. Through compromise during those

years Armenian writers managed to publish their

books and become "legitimate" creators.

Sevak was one of four famous contemporary poets,

who didn't become a member of the Communist Party.

People used to tell stories about his disobedience

towards the authorities. For instance, once he

was ordered to visit the Central Committee of

the Communist Party and was told that he had said

that members of the Central Committee are Turks.

Sevak answered that "Turks" is normal

as there are good people among them but you are

worse than Turks as you are not people.

Sevak was not a "legitimate person"

among all "legitimate persons", he was

the rebel among the temperate. He was the one

who could talk to the upper class of the Communist

Party but he always was a clown, who tells the

king all the truth:

"Clown"

You see, it is a child's play for me

To provide a plank with brain folds,

To prepare chicken-feed from brain,

And then a public meal of that chicken-feed.

However, one day his disobedience ran afoul and

the Central Committee prohibited publication of

his "Let There be Light" and protests

against his previously published poetry flooded

the Kremlin.

Subtexts and symbols of poems from "Let

There be Light" which secretaries of the

Central Committee dug out and found between the

lines, criticize Soviet methods. As it is written

in "Source of Light":

Our rear is a dark one indeed:

It's from books that we learn of our past;

Yet our front is darker still:

The books declare our future.

Darkness in front of, darkness behind us,

We are caught in between.

"Let There be Light" was published

in Beirut after Sevak's death. It brought the

times of nonconformist literature closer, but

it was not until several years later that it was

published in Yerevan. And even then, it had some

abridgements.

A society looking for the personification of

their protests against cruel methods and injustices,

discovered Sevak. And in 1971, when he died (at

age 47) in a car accident, hypotheses of Sevak's

death were spread. His death is still a mystery

and still discussed: Accident or murder?

"Those days I was deader than Sevak,"

says the poet's first wife Maya Avagyan. "I

couldn't come to my senses and I didn't ask whether

he was killed or not. Later I was asking one of

his friends, who was holding a high post in the

Party, of only one thing: to find that truck,

which was the cause of the accident, however,

they never found it."

She remembers Sevak sitting cross-legged on a

sofa for many hours and writing in his notebook.

She says he had only one weakness: women.

Sevak's funeral turned into national sorrow.

His body was taken from Yerevan to Sovetashen

village, where he was born. For 100 kilometers

those who loved him escorted his body, while fans

came out of villages to stand at the roadside

with lines from his poems written on posters.

Of his own art (in "The Birth of a Poet")

Sevak says:

The poet's "work is a bottle thrown into

the sea by a drowning sailor asking for help.

Will the Sea of Time ever bring the bottle ashore?"

A year ago waves of demonstrations brought ashore,

next to the Matenadaran, the bottle he had thrown

once.

To see the shores of verity,

To witness to the falsehood of the liar;

So that you will not be afraid

To unmask the face of injustice.

One has shouldered the world,

While the other is sitting on its shoulders.

(Poems translated by Marine Petrosyan)

|