|

The waste of the factory is being thrown into the Voghchi river. This is the water they use to water Kovsakan gardens. |

There is no epidemic in Kovkasan city or its suburbs but all residents say they are going to leave. The most frequently heard reason is we were deceived and if they keep their word it will soon be hard to find any residents here.

Conquered by Armenian military forces in 1993, Kovsakan is the former Azerbaijani city of Zangelan , bordering the southern regions of Armenia next to the Arax River . A year later it became the southern center of Nagorno Karabakh's Kashatagh region and a government resettlement program started.

When people used to leave before, it went unnoticed because others were coming to settle. Now nobody comes here, people only leave, says Khachik Adamyan, the Mayor of Kovsakan.

Kovsakan is a city only by name and the ruins of the former city. Two hundred families live there and 20 have left within the past two years. There is no telephone service or post office. Residents must bring in drinking water from far away.

Migrants were initially attracted to the area by promises of privileges and development prospects. Today, those privileges have decreased and the area declines rather than develops. In six years, only one hospital (with money provided by benefactors) and one school have been built.

Communication in the 21 st Century is a simple issue, but they cannot solve it. People are isolated from the outer world. People rely on the government to create such structures so that the territory can become a part of Armenia , says Adamyan, who took part in the war and was active in the Karabakh movement.

He moved here from Yerevan in 1998 and is raising three children. He says: Me and my friends came here full of dreams. We entered the city on April 24. We were ready to create a settlement.

|

The only comfort of Mamikon is the fruit he gets from the gardens. |

We were sure that it would become part of Armenia , its southern gate. I believed in the program but if I heard about it today I would never come. Discussions at the Council of Europe and the indifference of the authorities don't raise hopes in our hearts. He is referring to the report in January of the monitoring group of the Council of Europe on Armenia and Azerbaijan , which raised the issue of Karabakh and other conquered territories. Although the word other' was deleted from the text of the monitoring group's report on Armenia , it remained in the parallel report on Azerbaijan .

Residents are watching developments on the settlement of the Karabakh conflict closely, which concern them directly. The greatest shock for them came in 2001 when Vardan Oskanian, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, told A1+ TV that if there are residents there (in Zangelan), however painful it may be. if we get the desired status for Karabakh then all occupied territories except Lachin must be returned. (Lachin is a former Azeri region that forms part of Kashatagh and provides a road link between Armenia and Karabakh.)

The settlers of Kovsakan and neighboring communities were taken aback. On the one hand the authorities were encouraging repopulation of the territories and on the other talking about returning the land.

If they don't want to populate the territories why don't they tell us so that we could leave, says Mamikon Yavrumnyan, a 30-year-old teacher at Kovsakan school who arrived four years ago from Yerevan . He has married and become a father here.

When I decided to come here I was told that everything would be ok and that my house would be built very quickly. Up to now I've managed to build only one room by myself so that I could have a roof over my head, he says.

|

Julietta's son. There is not future for children in Kovsakan.. |

He repaired a room in a wrecked house with the aid of workers whom he paid himself. Authorities estimated the cost at 100,000 drams ($175) but gave him only 20,000 drams towards the work. Yavrumnyan has collected material to repair a second room but is unlikely to need it because he plans to leave. The authorities have constructed only three houses in the city: for the mayor, deputy mayor and chief doctor of the hospital.

Annually, 40 houses are built in Kashatagh for immigrants, all of them in Lachin, now renamed Berdzor. Elsewhere, migrants must do their own work, though the authorities will pay them up to 250,000 drams ($438) depending on the work involved.

Alexan Hakobyan, head of Kashatagh administration, doesn't say why houses are built only in Berdzor, but explains why they are not constructed in other settlements.

Construction of one house costs 3-5 million drams. Our budget remains the same but prices for construction materials have gone up. Heaven doesn't rain money. Those who will endure to the end will have houses.

Teachers are promised apartments only to find themselves in the streets when they arrive. So they combine classroom work with building a home.

Instead of giving me cattle credit they brought a calf. If I didn't take the calf I wouldn't have even that, says Yavrumnyan. The mayor did everything possible so that at least teachers could get cattle. Other people don't get even that. I sold my cow because I couldn't keep it. From morning I'm in the school and there is no herd.

|

Mayor of Kovsakan Khachik Adamyan.. |

Teachers were lured here by the promise of salaries that were 30 per cent higher than in Armenia . Yavrumnyan earns up to 47,000 drams ($82) a month, but the privilege has been erased as salaries in Armenia have risen to match those in the region.

They have to travel several kilometres to fetch drinking water. Yavrumnyan's two-year-old son fell ill last year from unclean water and had to be taken 50 kilometers for treatment in Kapan.

The only consolation is the subtropical climate with persimmon, pomegranate, fig and other gardens that allow teachers to survive. Even that small consolation comes with difficulties because the gardens are watered from the Voghjy River , which is silvery in color because of pollution from industrial waste at the Kapan Mining Plant.

People in Kapan don't buy fruits from the Turkish side (as they describe residents of Kashatagh) because they are watered with concentrate.

Artush Tsatryan. engineer at the Kapan Mining Plant, promises that this year waste won't be poured into the Voghjy River any more. They are going to install pumps that will direct waste to a special repository.

But not everybody has irrigation water.

It would be great if we had water as now we have neither drinking nor irrigation water. We have a ground area of 5,000 meters but cannot make use of it, says Julietta Markaryan , a nurse and a mother of five, who came here from Masis. The mayor promised them drinking water soon but it doesn't much console her.

I maintain my husband, otherwise, we would have left this place long ago, she says. With great difficulty, we built one room but they don't give us money for the house. We don't feel comfortable here otherwise we would have built another two rooms.

Snakes are another problem in Zangelan, appearing at people's feet when the weather gets warm. Julietta, who works at the hospital, says one or two people a day are brought in with bites and there were two deaths last year.

|

Vachik will not forgive anyone who tries to take metal from his territory. |

Snakes make us wish to leave this place. You work the land then suddenly notice a snake putting out its head, she says. Official indifference towards the residents has led to a resumption of plunder as immigrants struggle to make a living. Residents strip metals in the ruins and sell them to buyers from outside. They claim organizers of the plunder are protected by high-ranking officials in Karabakh and Armenia .

For 4 to 5 years there has been no plunder. But it has begun again. No matter how much they say trust in government policy', people instinctively feel what is going on and they can see the lack of attention to this area, says Adamyan. People plunder as much as they can - pipes, rail tracks, anything.

He walks through the streets takes sledge-hammers away from people, but loaded trucks pass police posts unhindered as they leave the area.

Now the iron rush has started, says Armen, one of those engaged in the trade. People pay 50 drams (about 8 cents) per kilogram. Within two weeks I can collect two tons and earn 50.000 drams ($87).

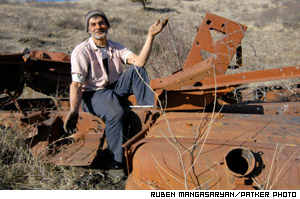

Selling metals is the only source of income of Vachik Mktchyan, who moved to Kashatagh from Yerevan. Together with his son he dismantles parts of an armored car left from the days of the war for a buyer to purchase next day. He says he participated in war, adding: Now I'm in a war for metal. They can live for a couple of days with the money earned until he finds another purchaser. This is his territory and he doesn't allow anybody to collect metal here.

|