|

Seventy-three-year

old Aregnaz Movsisyan gets up with the roosters to spend time with the cows. |

Against a horizon marked by an infinity of mountain and painted red

by sunset, villagers lean into sofas, taking rest at the end of the day in the

village of Nigavan. But this is Thursday, and 73-year old Aregnaz Movsisyan

turns her kind, thin face to an important work. She holds in her aging hands

an old-fashioned iron, moving it back and forth over a worn-out sheet. The finished

product is a shocking-white shirt that her husband, 74-year old Albert, will wear

tomorrow to the city. Like on other Thursdays, Albert is shaving and having

a bath, getting ready for another Friday's trip to Yerevan. With four red

10-liter cans full of matsun and glass containers, on Friday, Alik and dozens

of other villagers in Aparan's Nigavan village takes a small, noisy village bus

to Yerevan. There, he sells the matsun Aregnaz has prepared, to city people who

might never understand why the Movsisyans tolerate country living. "Civility

is everything," explains Alik, "the entire village is working to be

able to exist, however, among everything people appreciate not only the high quality

milk and matsun but the way villagers talk and dress appropriately as well. These

days there is a strong competition and everything you wear should be unspotted

so that you could sell your goods." Nigavan is about 65 kilometers

northwest of the capital and the bus ride takes about 90 minutes. Villagers

pedal their dairy goods in Yerevan's suburban districts such as Shengavit, First

and Third Districts, Malatia and Bangladesh. Depending on the villager and the

suburb, a liter of matsun sells for 100-200 drams (about 17-35 cents). On average,

each villager sells about 30 liters a week, earning enough money to return home

with provisions for the next week, such as rice, sugar, spaghetti. And with vegetables

such as tomatoes, because Nigavan's short growing season makes it impossible to

grow that Armenian summer-time staple.

|

It's

back-bending work, hauling water from a 12-meter well. |

Today Nigavan exists thanks to sheep and cattle farming, and to patience. Head

of the village Artash Galstyan says founders of Nigavan settled there in 1828,

during a deceptive spring. From Erzrum and Mush and Kars (now part of Turkey),

today's villagers' ancestors settled in Nigavan because of its lush green. But

that spring of 1828 was not typical. "Our village is located in a

territory having one of the worst climatic conditions," complains 64-year-old

Frunzik Hovhannisyan, who was carrying a book about religion, and is known to

be one of the village's more knowledgeable inhabitants. "Our winter lasts

eight months and spring lasts four months. And in such conditions villagers can

rely only on cattle breeding." And indeed, while the weather is boiling

in Yerevan spring coolness reigns in Nigavan and in the evenings it's even cold

there. The winter is tough. Every year villagers face snows of 1.5 meters. During

those days the villagers join together to clear a passage for the bus, so that

they don't miss their chance to go selling in Yerevan. Like other Armenian

villages, Nigavan was the site of collective farms during Soviet times. Everyone

worked together for the State. Today there are 155 households and 725 residents.

"Before it was rare when villagers had cows or sheep," says

the village leader. "However these days each household has at least four

cows and 7-10 sheep on average as it is the only way of existing in the village."

Houses

here are simple - a place for resting, following long days of cutting grass and

preparing for winter. Homesteads include cattle barns, hen houses, and rooms

with "tonirs" for making bread. Village houses keep the smell

of milk production - a heavy smell - as all families process their dairy goods

at home. Mattresses placed one on another are the pride of every house.

Mothers and grandmothers make them from sheep's wool as a dowry for their daughters

and granddaughters. And spread everywhere on the floor, black and white wool marks

homeowners as shepherds. For 10 years residents of Nigavan have been selling

hundreds of liters of milk and matsun in the capital every week. Sometimes they

sell sour cream, incomparably richer than that produced in cooperate dairies. Alik

and Aregnaz rise with the roosters at around 5 or 6 o'clock each morning. Aregnaz

milks three cows and sheep and then she makes cheese, matsun, butter and sour

cream. She cleans the house and makes a meal while Alik sends his cattle to pasture,

does some chores and, like other villagers, cuts grass so that animals could have

forage in winter. "Our small household takes care of several families,"

says Aregnaz. Part of what they produce also benefits families of sons and daughters.

"We don't complain. This is how we live." "Those two bullocks

are my grandchildren's payment for education," says Alik, referring to his

herd and to two granddaughters who are getting higher education in Yerevan. "My

grandchildren are students and all of us are working to help them stay in the

institute, as education is a great thing. We must help them as long as we can." Alik

and Aregnaz have earned the respect of other villagers, in part because they managed

to send their grandchildren off to study.

|

A

person who works hard could "live in a stone" Aregnaz says. |

There are approximately 160 children studying in the secondary school

of Nigavan. Schoolchildren dream of becoming actors, poets, famous singers, however,

they realize that it is only a dream for Nigavan villagers. There aren't many

children who study seriously. Either they cannot go to Yerevan or they just have

no time for study or they don't even think about it. "Children also

do a lot of work in the village," says teacher of Armenian language and literature

Gayane Grigoryan. "Of course it creates obstacles to their study. They are

working on the same house and household and after hard work they can't be romantic

enough to write a composition." Despite everything, teachers assure

that it is not possible to live through such conditions without being romantic,

and especially during wonderful spring weather senior schoolchildren sometimes

escape the lessons. There is no cinema nor Intenet in Nigavan. The only

television is the Public Channel, which doesn't interest youth that much. Older

residents watch the Hay Lur network and curse at the news. Young people

prefer escape into the mountains, where they can dream. These dreams are

about future education, leaving the village to find a different life, or about,

of course, marriage and creating families. Those who can afford it, attend

Mesrop Mashtots Private University in Yerevan, where a former resident of Aparan

is an official and helps the villagers get in. But most agree that the education

is of little result for anyone who plans to stay in Nigavan. "We have

many clever children," says director of the village school Nver Baghdasaryan,

"however, they have to stay in the village as they haven't got means for

leaving and as a result they don't get any professional education." The

director says that in such conditions when desire doesn't correspond to means

there are teachers who cannot take care of their daily needs with their 25,000

dram (about $43) salaries and they have to sell matsun like everyone else. "Today

teachers have no other choice," he says, "and if a child sees a teacher

in such conditions the possibility appears that the teacher could lose his or

her authority, however, today there is no other choice." More than

talks about education and study there are talks about marriages and love affairs,

which don't happen often enough during recent years.

|

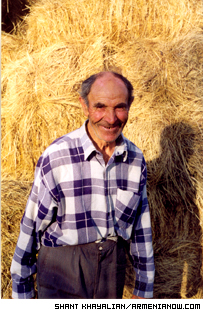

Albert

Movsisyan says villagers should give a good appearance when they go to the city

to sell their goods. | "Mainly parents see

and then choose a girl for their son. And the beginning of future marriages between

young people from different villages takes place in village buses, where villagers

selling matsun meet each other and boys find their girls," says one of the

villagers. "Then they ask for the girl's hand and if she agrees they get

married. Girls get married at an early age here, before they become 20. If a girl

is older than 20 and she is not married then it means she is a maiden." Medical

assistant of the village Tsovinar Sahakyan says a few years ago 20 to 25 babies

were born in Nigavan each year. Last year, however, only five babies were added

to the population. Two of those were born at home to parents who couldn't afford

to go to the hospital in Aparan, seven kilometers away. Sahakyan says she

has tried to encourage more reproduction in Nigavan. "I visit houses

and explain that women become more beautiful and younger after pregnancy. Some

villagers listen to me, some don't but I continue my agitation," she says.

"Maybe it will help." However, villagers don't think about becoming

more beautiful and younger. They mainly try to take care of their households and

increase their income. "Every year there are difficulties," says

Alik Movsisyan. "This year the problem is thousands of mice that have appeared

in fields. They damaged the work of villagers that has taken a whole year. Mice

have damaged all the barley that villagers have seeded for feeding their animals

in winter. The government promised to do something but the promise has profited

nothing and mice have already managed to eat the entire fields. "It

is not clear whether these mice are for us or for the government." It

is clear in Nigavan that what might be called "simple" living is hard

living. For example, water is gathered by lowering a bucket into a 12-meter well

and hauling up the load. But it is a life that can be managed. For most

there, it is the only choice. "Times have changed now," says

Aregnaz resting her hands upon her knees. "There's no sense to complain,

as there are still possibilities to live. There are no dependences and there is

an independence. "If villagers work hard then they can live. People

must work to live. If you work you can live even within the stone."

|