|

"I

blame my parents for bringing me into this awful

world. I think in the first place they are guilty

and then Chekists (former KGB member)," says

80-year-old Antonina Mahari wrapped in several

coats. Siberia comes to her Yerevan apartment

with the cold: at this moment its zero degrees

Celsius in the apartment. Sometimes it changes

to minus 1 or plus 1. "I

blame my parents for bringing me into this awful

world. I think in the first place they are guilty

and then Chekists (former KGB member)," says

80-year-old Antonina Mahari wrapped in several

coats. Siberia comes to her Yerevan apartment

with the cold: at this moment its zero degrees

Celsius in the apartment. Sometimes it changes

to minus 1 or plus 1.

"It is chilly here, but it is good I am

nor very hungry. Besides, I put on many clothes

to stay warm. But here I cannot have a shower.

There they were taking me to a bathhouse every

10 days."

"There" is Antonina's reference to

Siberia and her memories of exile.

Siberia hasn't left her alone even after returning

from exile. In one case it comes in the form of

cold and hunger as it is today. And in another

case in the shape of an inquisitor, as it was

in the 1970s, when her husband Gurgen Mahari's

novel "Burning Gardens" was burned under

their window. In other ways it comes as the death

of her daughter or her son's madness.

Siberia became a symbol of trouble which accompanies

her till today. And it is never far away.

Siberia started to crawl into Antonina's life

in 1945, when Soviet authorities replaced the

German army and began purging Lithuania of its

native children.

Chekists arrested 22-year-old student of Department

of Law Antonina Povilaytity on Vilnius's Street,

for her involvement in forming a patriotic group

to defend independent Lithuania.

"While being arrested my only feeling was

pride. I was proud that I was also a hero. Why

wouldn't they arrest me when all the others were

being arrested? This is what youth means."

There were 45 women in GPU (the former title

of KGB) building's basement taken to interrogation

every day and beaten. Men that "pleaded guilty"

and sentenced to death were waiting for implementation

of the penalty in the lower basement.

"They were beating so terribly during interrogations

that it was impossible to stand it. One girl went

crazy. A Polish countess arrested for being a

noble couldn't stand beatings and died. My face

was black of thrashing, but I was very quiet and

I wasn't afraid of their beating and cursing."

In 1940 when the Soviet Union first occupied

Lithuania Antonina watched as people with their

families were put into wagons and sent to exile.

Now, it was her turn together with thousands of

her compatriots.

"When they were taking us streets were deserted.

There was an impression that they took everybody.

They threw us into wagons, as we were some commodities,

closed doors and the train started."

She was sentenced to five years in prison and

was first taken with other prisoners to Autonomous

Region Komy, and then further to Omsk in Siberia.

They were placed in the barracks and taken to

work, which was 10 kilometers away on foot and

in the evenings taken back again on foot every

day. They were fed "balanda" (liquid

with few pieces of cabbage drifting in it) and

were let to have some sleep to go to work the

next day.

"The snow was starting to melt in May. It

was terribly cold there. I was cleaning hollows

of the trees from snow with a wooden spade for

men to saw them. Now I cannot stand snow.

"Many exhausted prisoners unable to cope

with the work were falling down and were shot

by guards right there."

These 60 years later, she remembers a Lithuanian

teacher that was walking on his way back and suddenly

fell down, got a bullet to his forehead and never

stood up.

"I was looking to the mirror and admiring

myself - bright blue eyes and long black hair,

which was rare among Lithuanians. And I couldn't

imagine I would die there."

The wife of a Minister of the Republic of Lithuanian

couldn't tolerate the torture and confinement

and hanged herself.

"She

had traveled all over the world. She told us what

to do to remain an interesting woman at a diplomatic

meeting two hours long, and that one must always

be in a good form. She couldn't imagine eating

without a serviette. She was used to the high

society life. Siberia wasn't for her and she didn't

cope with it. And I always had a hope to return

to Lithuania again, and then to escape abroad

and free myself from Bolshevik's authority forever.

Hope was empowering me." "She

had traveled all over the world. She told us what

to do to remain an interesting woman at a diplomatic

meeting two hours long, and that one must always

be in a good form. She couldn't imagine eating

without a serviette. She was used to the high

society life. Siberia wasn't for her and she didn't

cope with it. And I always had a hope to return

to Lithuania again, and then to escape abroad

and free myself from Bolshevik's authority forever.

Hope was empowering me."

Antonina tried to escape but was captured and

sent to another camp where she lost consciousness

for the only time in her life.

"There was a cruel face of the nurse in

front when I opened my eyes, and I regretted that

I was back to this world. There was a saying in

Siberia: 'Lucky is the one who wasn't born'."

Five years of imprisonment were passing and Antonina

was counting days left to return to her homeland.

But the Chekists had determined a completely different

destiny for her. After imprisonment she was sent

to Derzhinsk, where in the yard of an administrative

building a GPU officer declared: "Here will

be your life and grave." She was sentenced

to life in exile.

"Even that time I still had a hope that

one day I would be released. I felt there is nothing

eternal in this world."

In 1952 Antonina was sent from Derzhinsk to a

neighboring collective farm (kolkhoz) to bring

in the harvest with her exiled friend. This obligated

work was very depressing for women. Stableman

tried to cheer them up and said: "Don't be

so sad, there is a poet here, who looks after

pigs."

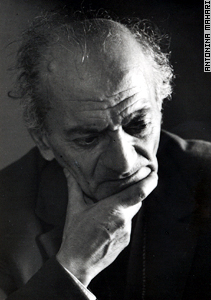

The pig tender was Gurgen Mahari, and one year

later Antonina married him.

Gurgen Mahari was among Armenian writers who

were arrested in 1937. Charents, Bakunts, Totovents

and Zabel Yesayan were killed (some shot and some

beaten to death). Mahari was sentenced to 10 years'

confinement, returned in 1947 and one year later

exiled again.

He was in hospital with a stomach ulcer and tuberculosis

and a nurse was expecting him to die in a few

days. But Antonina brought him back from the edge

of death.

"If a person there stays alone and there

is nobody to stretch a hand to him he will die.

Our Lithuanians were bringing milk to him, and

even eau-de-Cologne. Other patients envied Gurgen.

He was our person, and troubled so much as we

were. This wasn't love as people understand it

now, this was more than love. We were battle mates,

whose love was based on the concern of saving

each other."

Mahari wrote in a verse devoted to Antonina:

Why are you late spring-girl?

Why are you late my last anguish?

The most real hope for freedom woke up after

Stalin's death (1953) and the couple was released

from exile one and a half years later. This news

had a curing meaning for Mahari: "This means

I will live," Mahari said.

"We were congratulating each other. But

we were keeping sad faces. It is so good there

is a death without mercy to any dictator,"

Antonina says.

They returned to Yerevan in 1954 with their 4-month-old

daughter Nazik Ruta. Two months later Ruta died.

"My poor Siberian beauty. Her death was

my and Gurgen's big tragedy."

Thirteen years later Antonina visited Lithuania,

but couldn't find any of her relatives. She knew

her brother had escaped to America during the

war, but his whereabouts was unknown. There was

no one whom she knew to get information about

her relatives. Soviet and German troops had destroyed

Lithuania so much that many relatives lost each

other forever.

"I loved my parents very much. I begged

God to not let them die in my presence. I was

getting mad if they were away for a few hours.

And God concealed their death from me."

In 1966 Antonina was exiled again to Siberia,

this time because of Mahari's novel "Burning

Gardens", the story of Van, the writer's

native town and its resettlement of 1915.

The novel became a target of Armenian intelligentsia

and those daring to consider themselves as patriots.

For them, Mahari's supposition that Armenian revolutionaries'

antagonizing the Turkish government might have

been a reason for the Genocide was impermissible.

They also considered it immoral propaganda that

the main character Ohannes Agha had a sexual affair

with his dead brother's wife.

Antonina remembers reaction to her husband's

novel.

"They were throwing stones and garbage to

our balcony. The mailbox was full of anonymous

letters: 'Damned Turk'; 'Anyway we will kill you.'

They were throwing books to the fire. Gurgen was

waking up in the middle of night and shouting

'I cannot stand it'."

Mahari wanted to throw himself from the window.

He left this world terribly offended, saying on

his death bed: "I will go to have a rest

finally."

Mahari died in 1969 (at age 66), and their 15

year old son, Gurgen, got a mental disease one

year later.

"He

said when he saw his father dead: 'Now I understand

what is death. Man doesn't hear anything, doesn't

feel anything, doesn't understand anything.' Then

slowly he started to degrade. Somebody put a spell

on our family for sure." "He

said when he saw his father dead: 'Now I understand

what is death. Man doesn't hear anything, doesn't

feel anything, doesn't understand anything.' Then

slowly he started to degrade. Somebody put a spell

on our family for sure."

Mahari's destiny bound Antonina to Armenia, unfamiliar

for her, but with ties knotted by her life of

sacrifice for the Armenian writer.

After exile Mahari kept repeating to his wife

that he would die if she did not come with him

to Armenia. As he was dying, he asked her to stay

in Armenia and tell about her sufferings.

After Mahari's death Antonina was oppressed for

taking a dare and staying in Armenia while being

a foreign woman and for her attempts to perpetuate

the memory of the writer.

"They spat on the front door nameplate saying

Gurgen Mahari. They were knocking at the door

and shouting if I am making a museum for 'that

Turk's dog'. They were telling me to get out of

their country, which was not my place.

"One tried to hit me, but he didn't fortunately.

If Gurgen died surrounded with his relatives at

the top of his fame I wouldn't stay in Armenia.

I became a live witness of his sufferings. Now

I turned this home into a museum, which is being

show by TV from time to time. And I get happy

because in those moments Gurgen comes back to

life."

Gurgen Mahari's furniture, personal items and

old wooden case with exile clothes are preserved

as it was in the apartment. Faded walls of the

sitting room are covered with Mahari's pictures.

Antonina's dream is to publish a book of memories

"My Odyssey" (the short version of the

book was published in Beirut 10 years ago) - her

means of implementing the last will of her husband.

She dreams to return to Lithuania, where former

political prisoners enjoy extraordinary attention,

have privileges and high pensions.

"We cost as much as gold in Lithuania. They

care about us and publish our memories. Nobody

needs me here, nobody is interested in my book,

probably former Chekists still have some influence

and don't want the truth about those years to

be published."

But how to return to her homeland? To obtain

a visa she needs to go to Moscow. But where can

she get money and what would she do with her ill

son? It is easier to go to America, then to Lithuania.

There is still another reason Antonina is staying

in Armenia: for Mahari's 100th anniversary to

be celebrated next autumn.

"I am happy that all my life I was with

the defeated. Winners will survive without me."

Defeated Lithuania, defeated political prisoners,

defeated Mahari. And today when Armenia got its

independence and former political prisoners are

winners here, she is again with the defeated poor.

She and her son are among 51 percent of the population

living below the poverty level and among the 16

percent who are the poorest of the poor.

Antonina's pension is 4,500 drams (about $8)

a month. Her son's pension for being invalid is

3,000 drams (about $5), plus they get another

4,000 allotted for poverty - a total of about

$20. The "poorest of the poor" spend

about $1 a day. She and her son live on about

33 cents per day each, eating only oats in an

apartment she doesn't even think about heating.

Exiled for her politics, exiled for love. Exiled

now by indifference and slow solutions to sudden

social change.

"Authorities think we are those to expire

soon and don't care about us. Armenians are probably

cruel, as far as only murder and robbery rules

in this country."

|