|

When Andranik Asatrian decided to write a book about the Karabakh war he neither had intention to become renowned nor pretended to acquire the reputation of a historical writer.

|

An Azeri who married an Armenian, Raya Babaeva says “each death hurt . |

All that the 15-year old wanted was to share his thoughts about the war and of Armenia’s history.

“You don’t know, my Turk contemporary, the truth about the genocide, you don’t know the truth about the Karabakh war,” Andranik wrote. “The history you learn in school is false, so let me tell you how things were in fact.”

The 35-page book “To My Turk Contemporary” was issued last April in Stepanakert. Friends of Andranik’s family paid to have 500 copies printed and distributed.

Andranik was born in 1988, the year a movement began for Karabakh’s self determination from Azerbaijan.

“I don’t know if this book will be read one day by an Azeri or a Turk,” the young author says. “But if that day comes I hope it will help my contemporaries to better understand history.”

The teenager has pale memories of war. He was two when his family escaped from Azerbaijan to Karabakh. But he learned a lot about the war from veterans of war, including his father.

“While writing the book I was asking myself a thousand times: ‘Was it worth the sacrifice of so many lives to be independent’,” Andranik says. “Each war is a tragedy, but our history shows that Armenians could live in peace only through war.”

Few people in Karabakh have read Andranik’s book, but many would agree with the position of the young man toward the war.

Independence for the (estimated) 145,000 who now live in Karabakh came at the expense of some 30,000 Armenian and Azeri lives. Thousands more carry physical or emotional wounds and nearly every facet of life in Karabakh is influenced by the fallout from war.

“When someone says that Armenians defended Karabakh because it was the land of their ancestors, I can guess that the person was not in Karabakh during the years of war,” says Naira Hayrumyan, a reporter for “Azat Artsakh” (Free Artsakh) daily.

“I think people fight, not for the conquest of land, but for protecting their children, wife and parents, for rescuing them from violence and massacre,” she says.

Hayrumian’s husband, Arthur, went to war to defend his home and his newborn son David. He was killed in 1992.

“I don’t know if the war was inevitable,” Hayrumian says “but I believe that people’s lives were not given in vain.”

If the reason for fighting was to gain freedom from Azeri oppression, then Hayrumyan may be right.

|

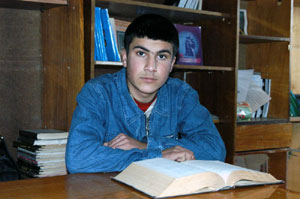

The author of “To My Turk Companion”. |

Karabakhi photographer Georgi Ghazarian says Azeris systematically suppressed the cultural life of Armenians in Karabakh.

Ghazarian recalls, for example, a time when it was prohibited to take photographs of Dadivank monastery in Mardakert. Only those who got special permission from Azerbaijan authorities were allowed.

“The Azeris made the territory of the monastery into pasture,” Ghazarian says. “They destroyed many ancient cemeteries in Shushi, constructing roads there. That was part of Azerbaijan’s state policy directed to expunge historical record and remove all evidence of Armenian presence throughout the region.”

The war that prevented further elimination of an Armenian presence in Karabakh made refugees of some 360,000 Armenians. Most fled pogroms and massacres in Baku and Sumgait, leaving behind 92,000 houses.

Those who left their homes for Armenia and elsewhere, fled to find unexpected problems in a new world of unwanted realities.

Nona Agabalova, 35, is a refugee who enjoyed a high social status in Azerbaijan, as part of a university research team. Today she lives in a hostel on the property of HayElectroMash plant in Yerevan, in a room that hardly has space for a bed, sofa and table.

When she speaks about the war and refugees she says that in her case “history repeated itself”. Her grandparents survived the genocide of 1915 of the Ottoman Turks and settled first in Karabakh then moved in 1933 to Baku.

“I do not want to blame my ancestors for choosing a wrong place to live,” Agabalova says. “I just wonder how after all they experienced, they went to live with Azeris.”

Her father died many years ago in Baku and her mother died recently in Yerevan, never reconciling herself to a life of “refugee” status.

“If I have chance I would like to visit Baku one day,” she says. “But I will never take the chance to live there. I don’t want to repeat my ancestors’ mistake.”

Armenians of Karabakh say they had friendly relations with Azeris during Soviet times. But their life was limited by a non-written law: “first Azeri, then Armenians.”

“If someone from Karabakh happened to get a job in a state university, he would not even get a ride to work. Such jobs were appointed by the State,” says Roma Karapetian, head of Nor Maragha village in the Mardakert province.

|

Levon Dabaghian says in case of war “I will take weapon and go fight”. |

“In fact they did not get such jobs. Some one who graduated from a university in Yerevan had to go to Baku to be approved. In Baku, they would say ‘You graduated in Yerevan, go find a job in Armenia’.”

Levon Dabaghian, 73, escaped from Kirovabad in 1990 and lives now in a home for the elderly in Stepanakert.

“All that I know is that Armenians always had to fight to protect their rights,” he says.

“We enjoyed a good life living with Azerbaijanis but we always knew that we can not trust them. We can blame authorities, but maybe it was our fault, those, who lived in Azerbaijan. It turned out that we were punished by history for trusting the Azeris.”

Dabaghian has no family. His only son died during the war. The old man spends his day gardening. And he follows news concerning the Karabakh-Azerbaijan peace process.

“The new president of Azerbaijan says they are ready to restart the war. Ilham Aliev thinks that he can follow the policy toward the elimination of Armenians, but he is wrong. Now my instruments are a spade and a rake. But if there will be a war I will take a weapon and go to fight.”

While the youth of Karabakh learn war as history and the elderly swear oaths they’d be unlikely to guarantee, many in between live with the war’s effects and ponder a future shaped by conflict.

For Almaz Antonova of Stepanakert, the war was deadly in a way more subtle than bombs or bullets. She is from an ethnically mixed family, with an Armenian mother and Azeri father. Her husband is Armenian. One of her brothers is married to an Armenian, another to an Azeri.

The war divided her family. Her parents moved to Azerbaijan, where her mother soon died, grieving over her divided family. Recently Almaz learned that her father died too. The brother who married an Armenian moved to Russia.

“War always affects ordinary people,” she says. “The war did not kill my family members but it changed all our lives.”

The war destroyed the family of another Azeri woman who lives in Stepanakert. Both Raya Babaeva’s parents were Azeri, but she married an Armenian.

“It was a hard time for me. Azerbaijanis and Armenians were killing each other, and each death hurt me,” Babaeva says. Her husband was among those killed when the Azeris bombed Stepanakert.

Both women lead normal lives in Stepanakert, which several years ago was an epicenter of war between Azeris and Armenians.

Antonova teaches Russian language and literature. Babaeva works at Artsakh Public TV and Radio, reading news in Azerbaijani. Her program “Voice of Justice,” is broadcast in Azerbaijan and directed toward establishing cultural ties between countries.

|

“War always affects ordinary people,” says Almaz Antonova. |

“Armenians accept me as one of their own and I have no reason to feel isolated,” Babaeva says.

“I am a patriot and to some extent a nationalist,” says Babaeva’s colleague Larisa Grigorian. “But I see no reason to hate Raya. It is not her fault that her people turned out to be hostile. I see no difference between her and my Armenian friends.”

For some, like Ashot Arakelian, economic hardship made worse by war was injurious, with wounds that are still unhealed.

Arakelian is a retired math teacher, who went with his son to Russia looking for work during the early ‘90s when Armenia’s economy was at its worst.

He found a job selling fruit in a market in Siberia. His boss, Ali, was Azeri, who escaped from Azerbaijan with his Armenian wife. Four years ago Arakelian, now 53, returned to Yerevan.

“I think the major reason of war was the collapse of the Soviet Union,” Arakelian says. “Ethnic conflicts appeared throughout the Soviet territory, such as in Chechnya, Pridnestrovie, and Abkhazia. Karabakh was one more conflict zone.

Did the war affect my life? Yes. Do I want to live as before, during Soviet times? No. That life was safe but not endurable. For many thousands of Armenian refugees dispersed throughout the world and Armenians in Yerevan who faced hard social problems, it is hard now to give a historical appraisal to the war. But I am convinced that our descendants will say that it was a salvation for the Karabakh people.”

Photos by Georgy Ghazaryan

|